a history of reporting on the South's poultry industry

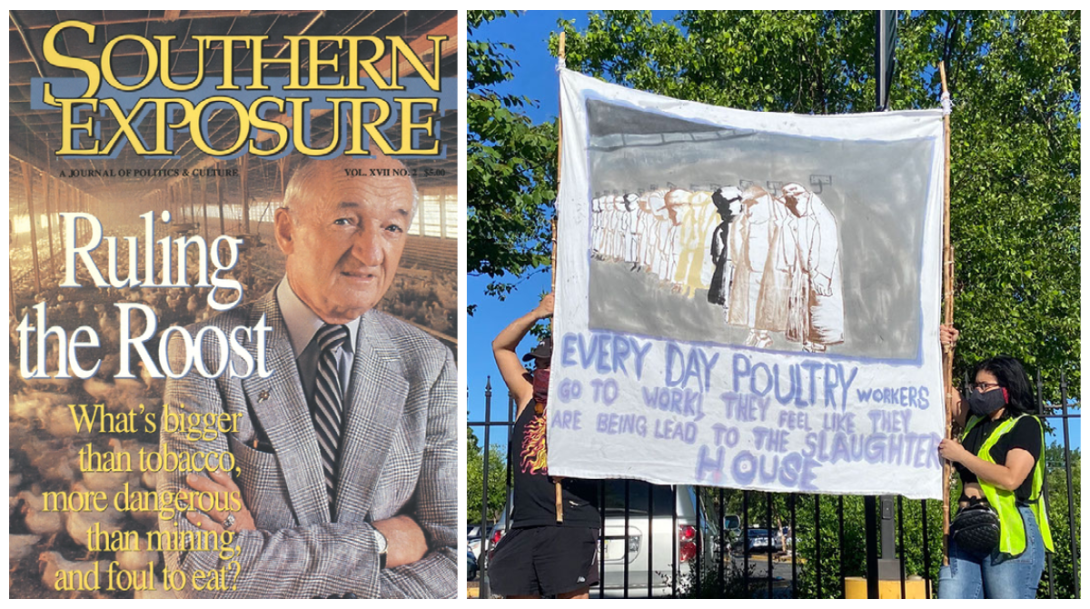

If you've been following my work over the past year, you know I've been hyper-focused on how the pandemic impacted poultry workers in the South, especially in Arkansas. When I pitched this investigative series last fall, I told my editor that I wanted to model it off of Ruling the Roost, a 1989 issue of Southern Exposure (a print magazine published by the Institute for Southern Studies, which now publishes Facing South), which was one of the first deep dives into the exploitation and concentration at the heart of one of the region's largest industries. The issue won a National Magazine Award. Legend has it that poultry organizers in North Carolina referred to it as their organizing Bible for years after it was published.

Today at Facing South, we published a package I've been working on for the last several weeks. For the first time ever, you can read three of the articles from that groundbreaking issue of Southern Exposure online. One is a deep dive into industry consolidation, the second a look at working conditions in poultry slaughterhouses, and the third an interview with Donna Bazemore, a Perdue worker-turned-organizer in rural North Carolina.

As I write in the introductory essay to the package, reading these 32-year-old feature stories alongside the investigations I've been reporting over the last year made clear to me just how persistent the poultry industry's problems have been — low wages, dangerous working conditions, retaliation against worker organizing. I hope that republishing them at a time when poor conditions in the poultry industry have made consistent headlines will drive home the same point for our readers.

One of the biggest things that's changed between 1989 and 2021 is the demographics of the poultry industry. In her 1989 interview, Donna Bazemore talked about the particular challenges of being a Black woman on the processing line in an industry where supervisors and executives were almost exclusively white men.

Today, the poultry workforce in the 5 largest poultry producing states remains 40% Black, but is nearly one-third Latinx, many of them recent immigrants. The second new piece in this package is my interview with organizer Magaly Licolli of the Arkansas workers' justice center Venceremos about her experiences organizing Spanish-speaking poultry workers in Springdale, Arkansas, where Tyson and several other poultry companies are headquartered. We spoke about why she organizes in a workers' center rather than through a union, her experiences as a Mexican woman in white and/or male spaces, and why she now calls herself an organizer, not an activist. An excerpt from our interview, which is well worth reading in full:

I found that the leaders in the community didn't really want to talk about those issues. Then I began understanding the complexity of the nonprofits that were receiving funding from Tyson and therefore they couldn't talk against Tyson. They were praising Tyson for all the charity that they were giving to the community, but in my head I was like, this is just — this is outrageous. They are creating these crises with our communities and then instead of helping these people, these workers, they are giving money to these organizations to help these workers. By doing that, these organizations cannot stand against the roots of the problem.

They're pretty much controlling the community by giving charity. Charity is not the same as justice. To me that was very clear. The charity is not fixing the problems, it's just creating the problems, and creating this cycle of poverty, this cycle of injustice. This is not solving anything whatsoever.

Rereading and resurfacing journalism from the archive is one of the most rewarding and humbling parts of my job. As journalists, the things we write are rarely new and groundbreaking — they're built on decades of past research, reporting, actions, and organizing, and they serve as a foundation for work to come. And that's how we work our way towards more just systems — building on each other's work, not going it alone.